The origins of PsychoPy

The seeds of PsychoPy were planted in early 2000s when Jon Peirce was a visual neuroscience postdoc at NYU. Jon had been using Matlab for his PhD and postdoc work but he was never really a programmer. He was just a psych/neuroscientist using code for his needs.

Although Jon had no formal computer science training, like many scientists, he became reasonably fluent in programming. He was using Psychophysics Toolbox but, in those days, PsychToolbox couldn’t do all the things it can now - stimuli had to be precomputed as movies, or you had to use sneaky tricks like “lookup table animation”. Those tricks are now long since forgotten (thankfully - they were clever but mind-bending).

The beginnings of PsychoPy

Around this time, there was a lot of talk about “hardware accelerated graphics” and Jon went through the tutorials for using OpenGL. He saw that this would allow a pretty great way to create stimuli that could be generated on the fly, and that meant not having to pre-computer movies in order to generate, say, a drifting Gabor. Jon was pretty excited that this was the way to go for stimulus rendering and he also found that in Python he could execute these OpenGL calls directly in his scripts.

Now, in 2002, Python was not well-known and in many ways was in its infancy (bear in mind that numpy wasn’t created until 2005!) but Jon was pretty excited by this and set about creating his first stimuli that combined textures (gratings and gaussian blobs) in useful ways to create stimuli like Gabors. It was all done relatively efficiently on the graphics card with really minimal easy-to-use scripts.

That was the beginning of PsychoPy, which was uploaded to sourceforge.net as psychpy in March 2002 (the “o” got added later but sourceforge didn’t allow names to be changed after registration, so it’s still there on sourceforge).

In 2003, Jon moved to Nottingham University as a Lecturer (Asst Prof, in American terminology) and began using PsychoPy for his own studies from then on.

Python enthusiasts

In the early years PsychoPy had a few users, a web page, a Google Group, but Jon didn’t really provide much in the way of formal support. PsychoPy was for his lab and he made it available, but if it didn’t work for you on your system that was… well, just unfortunate! Actually, that’s not quite true. Jon discovered that the power of Python meant that he could add things with relatively little effort and so he often spent his evenings and weekends adding features that users requested. He added more stimuli, and the Coder interface, and built the dependencies into an app so it could be installed more easily. That set of features led to the first manuscript about PsychoPy in 2007 (Peirce, 2007).

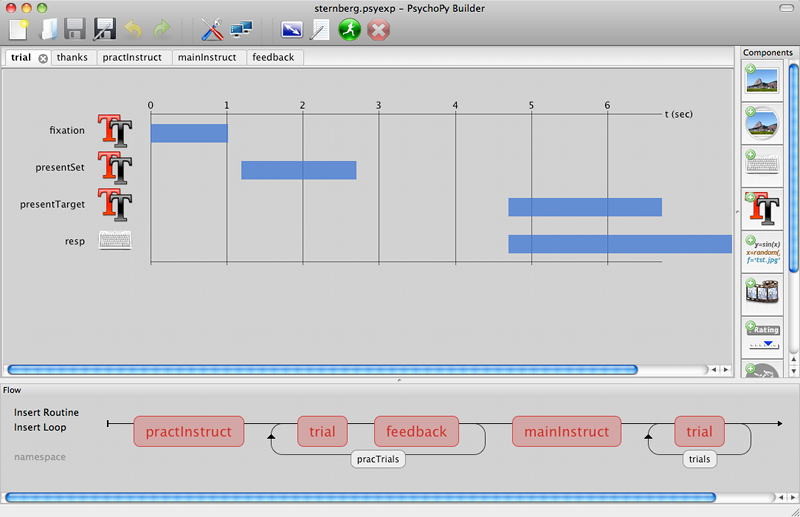

2008-9 Adding the Builder interface

Jon was teaching psychology undergraduates to use E-Prime in their practical classes at Nottingham. That wasn’t suitable for psychophysics stimuli (it couldn’t create the sort of stimuli that vision scientists need) but it was the only software at the time that had a simple enough graphical user interface for undergraduates (and other non-programmers) to create their own studies. Some discussions with André Gouws at the University of York, encouraged Jon to think about what an ideal graphical interface would look like for PsychoPy and to work out the mechanics of what that might do. This was the beginning of creating the Builder interface. It was a lot of work, mostly in evenings and weekends, but by 2009 this was available with a range of simple stimuli and flow controls, as well as the option to add code snippets. It meant that people could use PsychoPy who didn’t have any programming experience and it quickly gained traction as a teaching tool. The inner workings of the Builder interface have changed very little since that first iteration, although the stimuli and user interface have improved enormously.

Increasing uptake, increasing features, increasing precision

With a graphical interface the userbase gradually grew. Increasing numbers of departments started using PsychoPy instead of E-Prime (which is expensive and less flexible in the stimuli it can present). This also marked a slight change in direction for PsychoPy because while Jon’s own research was in visual neuroscience, the increasing userbase was more in cognitive psychology and linguistics, areas that particularly valued the graphical user interface.

As the user numbers grew Jon, and additional contributors like Sol Simpson, Jeremy Gray and Richard Höchenberger, were working fairly continuously adding further features, like eyetracker support and asynchronous hardware polling, more stimulus types and response options, and generally making the Builder more capable of running studies that were as precise as hand-written code. Indeed, this got to the point that Jon himself started creating his own experiments in the Builder interface rather than by hand (not something he had expected to be doing!).

As PsychoPy grew, however, it became hard to keep up with the support needs on a part-time basis while Jon and the contributors had a range of other commitments. There were increasingly frustrating situations where we would know that a bug existed but couldn’t spend the time fixing it because of other commitments (like marking undergraduate exams).

Grant funding

Ultimately, what rescued the situation was a grant from the Wellcome Trust to port PsychoPy to an online platform (PsychoJS and Pavlovia), followed by a grant from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. These grants made it possible for a small team to work full-time on improving the software, documentation and training in the PsychoPy ecosystem.

PsychoPy now has too many users for us to contemplate going back to a volunteer-based part-time development model. We absolutely depend on the revenue that comes from Pavlovia site licenses and from consultancy work for users in order to provide full-time staff dedicated to the project. That is now possible, thankfully, managed by our social enterprise company, Open Science Tools Ltd.

We hope that this model of development, in which the software is provided for free (PsychoPy will be open source always), but with full-time develoment paid for by services, is a useful business model for the future, and potentially for other projects. We hope it means quality can be free to the masses, while also being of a professional quality.

We hope you enjoy using the modern PsychoPy, and thanks for supporting the project in your various ways.